Finding Time with the Neuroscience of Transformational Leadership

I enjoyed reading a recent interesting article in the New York Times titled, “Can We Slow Down Time in the Age of TikTok?” This article was inspired by a college art professor’s efforts to have her students slow down enough to see and experience the world, instead of making everything completely utilitarian. The general idea is that understanding and sensibly managing time in ways that allow you to just be present in the world has immense value

In one section, the writer alludes to the spread of “mindfulness” in corporate environments as a version of this, tying the pauses created by mindfulness to evidence that these pauses create productivity gains. This note definitely grabbed my attention because I was preparing to give a talk on the “Neuroscience of Transformational Leadership” and the pressures and opportunities of “time” as a central part of my talk.

Spurred by the many issues that I see related to time in our work, and aided by Dan Pink’s excellent book about time “When,” I have come to see understanding and managing time as one of the most critical aspects of effective leadership, particularly leadership during a significant transformation.

The first issue that I see is that intensive time pressures acts like a threat stimulating a fear response. In this situation, people’s brains produce adrenaline (the neurochemical of hyper awareness) and cortisol (the fight or flight neurochemical). At the same time, time pressures overload their pre-frontal cortex (the “intelligent” portion of the brain) as it tries to process lots of information in short, intense bursts caused by various deadlines and projects.

Prolonged exposure to these situations are known to cause long-term health issues. And, from a leadership perspective, prolonged exposure causes a degrading of decision-making. Leaders working under these conditions consider fewer alternatives, do less analysis and get fewer inputs from others. In short, under these pressures, leaders jump to conclusions and actions – often bad ones.

More generally, time pressures are an issue for leadership and organizations in many ways:

- People are already working so hard, that they can’t work any harder without detrimental effects. So, if an organization wants to improve performance, people have to work smarter, which requires time to think. The slogan is “work smarter, not just harder.” The paradox is that, in order to work smarter so you don’t have to work harder (which you can’t do anyway), you have to stop working harder for long enough to think. To work smarter, you have to stop working so hard – which is very hard for people to do.

- There is an incredibly strong norm about working hard and being busy. Afterall, being busy means you are important. As a result, people take much pride in being time squeezed and organizations see being time squeezed as an indication of someone working really hard, and making a contribution. Of course, the irony is that, from a time utilization perspective, being important should work in exactly the opposite way. You want your best people being thoughtful – i.e. working smarter – because that creates leverage for the organization. When was the last time that you heard someone say – I am so good at my job and smart about the way I do my job that I am NOT time-pressured. Or, how about an organization saying, you are so important to us that we want you to work less and think more. That should be the value, but it isn’t.

- These norms seem to be particularly true for executives. When was the last time you heard an executive say – I want to give lots of time to that issue because it is really important and I want to learn about it and think about it? Instead, most executives manage their time in dysfunctional ways. For example, we just tried to do a demo for a leadership team that had a very specific, well-defined leadership development issue. They had created a new role in the organization and needed people to become good at the role quickly. We had worked with this type of situation many times and knew that it takes 90 minutes for executives to learn how to develop the role and answer all their questions…and, of course, they gave us only 60 minutes. There are always one of two results for executives in this situation – they make a decision on incomplete information, almost always rejecting a good option (see above about bad decision making) or they have to schedule additional time which actually requires more overall time. Being a time-squeezed executive usually is counterproductive to good leadership.

- These factors are particularly important during a transformation. Time functions very differently during a transformation than in a situation of well-established operational processed. When an organization is operationally excellent, time tends to function in a fairly linear, cause and effect way. You do something and it has a predictable result in a predictable time frame. This is not what happens during a transformation. Time is decidedly non-linear in the sense that cause and effect are not well connected. You do something and it may or may not produce a desired result and it may or may not occur in the desired time frame. If an organization and people in the organization treat time as linear during a transformation — which is the natural tendency – and transformation time is actually happening, everyone gets very frustrated and lots of conflict emerges.

As may be apparent, there is lots more to time in organizations than simply thinking of mindfulness.

So what can you do about this? We have three suggestions:

- Consciously be responsible for your own learning by carving out time to learn – be a self-directed learner, not a passive reactor to time pressures

- Consciously set aside time to be thoughtful. This isn’t just mindfulness but setting aside even as little as five minutes a week to think

- Focus on the intangibles of being great as a leader – a lot of which is working smarter not harder

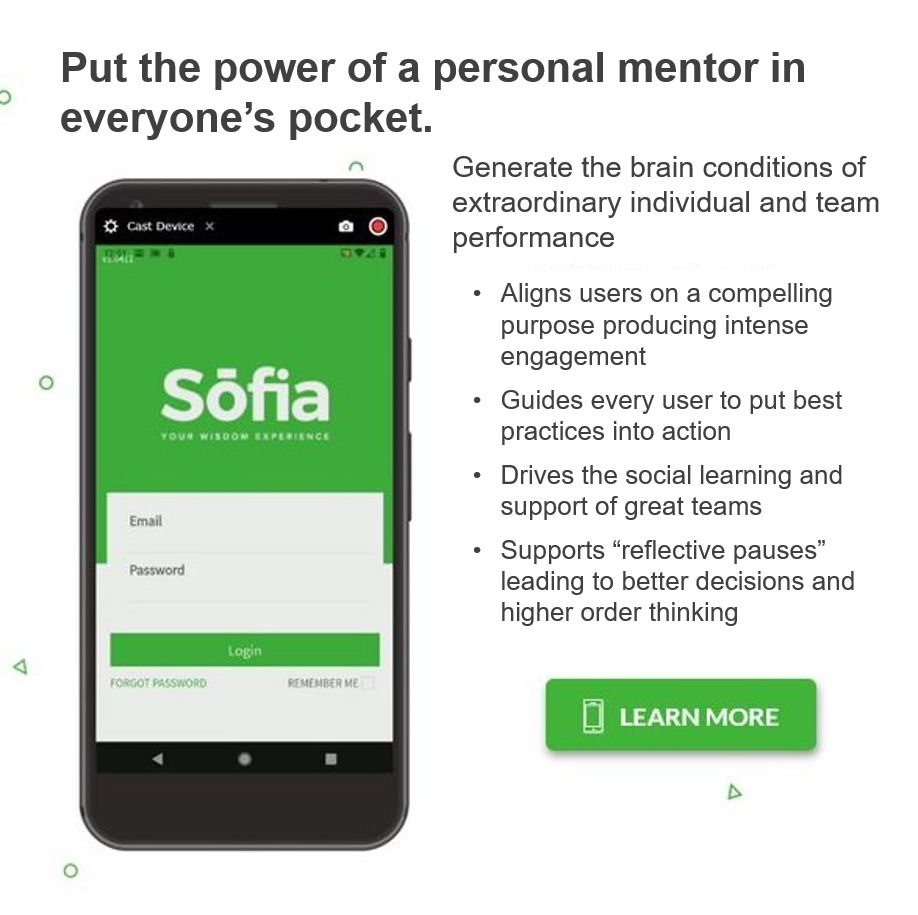

At Cerebyte, our programs carve out one hour every two weeks to focus on working smarter not harder. During this one hour, people discuss their learnings from 30 minutes of focused, practical actions per week – what they learned and how they could work smarter, not just harder.

The results are staggering. Productivity and morale gains are huge and it is just a little carve out of time. It would be worthwhile for you to take a pause and ask yourself, “Are you working smarter, not just harder?”